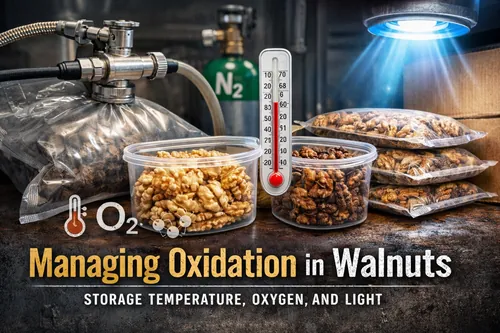

Managing Oxidation in Walnuts: Storage Temperature, Oxygen, and Light

Industrial guide for managing oxidation in walnuts: storage temperature, oxygen, and light are the three big levers that determine shelf-life performance. This article explains why walnuts oxidize, how oxidation shows up in sensory and QA results, and what buyers can do—through format selection, specs, packaging, warehousing, and logistics—to keep bulk walnut programs stable.

Previous: Specifying Defects and Color for Walnut Kernels: Buyer Checklist • Next: Seasoned Walnut Snack Programs: Oil Management and Flavor Adhesion

Related: bulk walnut products • products catalog • request a quote

Buyer lens: Oxidation is often the #1 shelf-life limiter for walnut kernels. The “fix” is rarely one thing—it’s a chain: quality at receipt → moisture control → oxygen exposure management → temperature discipline → packaging fit → inventory turns.

Table of contents

- What oxidation is (and how it shows up in walnuts)

- Why walnuts are oxidation-sensitive

- The three big levers: temperature, oxygen, and light

- Format selection: halves, pieces, meal/flour, oil—how surface area changes risk

- Storage program design: warehouse rules that protect shelf life

- Packaging options for bulk programs (liners, barrier films, vacuum, inert gas)

- Specs checklist: what to confirm on contracts and COA

- Handling opened packaging in production

- Shipping and logistics: heat exposure, transit time, and landed-risk planning

- Troubleshooting oxidation complaints: practical root-cause map

- FAQ

- Next step

What oxidation is (and how it shows up in walnuts)

Oxidation is a set of chemical reactions where fats react with oxygen, creating compounds that change flavor, aroma, and sometimes color. In walnuts, oxidation is commonly experienced as rancid, stale, painty, cardboard-like, bitter, or “old oil” notes. These sensory changes can develop gradually, which is why the earliest signs are often subtle and show up first in sensitive applications.

From an industrial QA perspective, oxidation risk is not only a sensory issue—it’s a predictability issue. If a walnut lot oxidizes faster than expected, you can see inconsistent finished-product flavor, more QA holds, or shortened best-by windows. For manufacturers, that can trigger rework, returns, or brand risk.

Common “symptoms” buyers encounter

- Shorter shelf life than expected even when initial COA looks acceptable.

- Off-flavor after roasting (roast can reveal oxidation earlier because heat volatilizes compounds).

- Batch-to-bF&Dgatch variability when the same spec performs differently across lots due to storage and oxygen exposure differences.

- Color dulling or uneven appearance in some formats (application-dependent).

In practice, oxidation is best managed as a system—not a single spec line—because it depends on time, temperature, and exposure conditions across the entire supply chain.

Why walnuts are oxidation-sensitive

Walnuts are naturally rich in polyunsaturated fats. Polyunsaturated fats oxidize more readily than monounsaturated fats, which makes walnut kernels inherently more sensitive to storage conditions. The industry implication: walnuts can be “high value” and “high nutrition,” but also high handling discipline.

Oxidation rate is influenced by the fatty acid profile, surface area exposure, existing oxidation level at packing, and how the lot is handled afterward. Even if two lots look similar at receipt, small differences in exposure time to heat or oxygen can create noticeable shelf-life differences later.

Key idea: Oxidation is cumulative. The lot “remembers” every warm dock, every opened bag, and every day exposed to air. Good programs reduce total exposure across time—not just at one moment.

The three big levers: temperature, oxygen, and light

1) Temperature: the speed control for oxidation

Temperature is the strongest day-to-day lever because it affects reaction speed. Lower temperatures slow oxidation and protect shelf life. Higher temperatures accelerate oxidation and can quickly convert a stable lot into a shorter-life ingredient.

For procurement planning, temperature should be treated as part of the product spec—even if it’s not printed on the COA. If your program requires long shelf life, ask how the product was stored prior to shipment and plan your receiving and internal storage accordingly.

2) Oxygen: the fuel

Oxidation requires oxygen. That means the “oxygen story” includes everything from packaging headspace to repeated openings in production. Lower oxygen exposure generally extends shelf life. This is why barrier liners, vacuum packing, and inert gas flushing can be valuable tools.

The practical buyer question is: How much oxygen exposure will the lot experience from packing to consumption? If you open a bag and use it slowly over weeks, your internal oxygen exposure may dominate the shelf-life outcome even if supplier packaging was excellent.

3) Light: the accelerator

Light exposure—especially UV—can accelerate oxidative reactions. For bulk warehouses, light is a “silent variable.” Kernels stored near open dock doors or in bright areas can experience more exposure than the same product stored in dark, enclosed conditions.

Light control typically means: avoid prolonged exposure during staging, protect pallets from direct light where possible, and use packaging with appropriate opacity or barrier properties for the program.

Format selection: halves, pieces, meal/flour, and oil—how surface area changes risk

When buyers choose a walnut format, they are also choosing an oxidation profile. The biggest difference is surface area: more exposed surface area generally means faster oxidation because more fat is exposed to oxygen.

Walnut halves and large pieces

Halves and larger pieces have lower surface area per unit weight, which can reduce oxidation rate relative to smaller cuts. They may be preferred for applications where sensory targets are high and shelf-life demands are long. However, they can be more sensitive to breakage and handling, which may influence yield and cost.

Small pieces, meal, and flour

Smaller cuts and milled formats increase surface area substantially. They can be excellent for bakery, bars, and inclusions where uniform distribution is needed, but they require tighter packaging, stricter temperature discipline, and faster inventory turns.

If you use milled walnut products, confirm particle distribution (mesh/size), flow properties, and—most importantly—storage and packaging suited to oxidation control.

Walnut oil and butter/paste formats

Oils and butters concentrate the lipid phase and can be sensitive to oxygen exposure and light. Drums/totes should be handled with care: minimize headspace exposure during use, keep containers sealed, and store away from heat and light. If your program requires consistent sensory performance, align on filtration/refining notes, sensory targets, and storage/handling protocol.

Storage program design: warehouse rules that protect shelf life

The best packaging in the world cannot overcome poor storage. For bulk walnut programs, a storage program is a simple set of rules that reduce cumulative exposure: keep the product cool, keep it sealed, keep it dry, and keep it away from strong odors and light.

Core warehouse practices

- Temperature discipline: avoid prolonged staging at ambient temperature during receiving and picking.

- Humidity awareness: moisture uptake can create texture issues and may increase shelf-life management risk.

- FIFO inventory rotation: first-in-first-out reduces the chance a lot sits long enough to develop issues.

- Dock management: warm docks and open doors can be a repeated heat/light exposure event.

- Odor control: nuts can absorb odors; keep away from strong-smelling materials where possible.

Inventory turns as a control tool

If you can’t justify more expensive packaging or chilled storage, faster turns can still control oxidation risk. In procurement terms: match purchasing quantities and delivery cadence to your production usage so product doesn’t sit.

Packaging options for bulk walnut programs

Packaging is essentially oxygen and moisture management plus handling protection. The “best” packaging is the one that matches your required shelf life, your distribution environment, and how you use the product after opening.

Common bulk packaging formats

- Lined cartons / bags: common for kernels and pieces; liner selection affects barrier performance.

- Sealed barrier liners: higher barrier films reduce oxygen ingress during storage.

- Vacuum packaging: removes headspace oxygen; useful for sensitive programs and longer storage windows.

- Inert gas (nitrogen) flush: displaces oxygen; useful when vacuum isn’t practical for the format.

- Drums/totes for oils: should be sealed, stored cool/dark, and managed to minimize headspace exposure.

How to choose packaging: a practical decision map

Ask three questions:

- How long will the product be stored before use? Longer storage usually warrants stronger barrier and oxygen-control packaging.

- What is the temperature and climate exposure? Warm climates and long transit times increase the value of higher protection.

- How will the product be consumed after opening? Slow-use operations should plan resealing protocols and smaller pack sizes where possible.

Buyer pitfall: Choosing a premium oxygen-control pack, then leaving opened bags unsealed on a warm production floor for days. Your internal handling can dominate the shelf-life result.

Specs checklist: what to confirm on contracts and COA

Specs are the shared language between procurement, QA, and suppliers. For oxidation control, you want to confirm both product specs and handling specs. Below is a buyer-friendly checklist you can adapt to your program.

Product specs (typical)

- Product form: halves, pieces, meal/flour, oil, butter/paste.

- Size / cut spec: halves and pieces definitions; for milled products, mesh or particle distribution.

- Moisture target: confirm your internal requirement and the supplier’s typical range.

- Color grade and defect limits: align with application needs (visual vs functional).

- Micro requirements: category-specific (snacks, ready-to-eat, bakery inputs).

- Sensory expectations: define “clean, fresh walnut flavor” and confirm supplier’s QA approach.

Handling/storage specs (often missed)

- Packaging type: liner specification, barrier level, vacuum or nitrogen flush if required.

- Storage temperature guidance: recommended storage conditions and maximum exposure guidelines.

- Shelf-life definition: how shelf life is counted (from pack date) and what conditions it assumes.

- Lot traceability: lot codes, pack date, and how to match documentation to receipts.

- Transport expectations: transit time, temperature management expectations, and seasonal shipping precautions.

If you’re building a new supply lane, request typical documentation early: COA, microbiology (if applicable), allergen statements, country of origin, and any supporting compliance documents used in your category.

Handling opened packaging in production

Many oxidation issues originate after the product arrives at the plant. Once a bag is opened, you effectively change the product’s environment: oxygen exposure increases, and temperature may rise if the product is staged near equipment or docks.

Practical best practices

- Reseal quickly: minimize open time; use clips or resealable liners where possible.

- Use smaller units: if a line consumes slowly, consider smaller pack sizes rather than leaving large bags open.

- Control staging temperature: avoid prolonged warm staging; return unused product to controlled storage.

- Protect from light: keep open bins covered where possible.

- Track open time: a simple label (“opened on”) can reduce “mystery aging.”

If you are roasting walnuts, note that heat can expose oxidation issues earlier. A lot that seems “okay” raw may show off-notes after roasting because heating accelerates volatilization and highlights older oil notes.

Shipping and logistics: heat exposure, transit time, and landed-risk planning

Oxidation risk increases with heat exposure and long transit time. For export destinations or long domestic lanes, plan your shipments with a “heat map” mindset: the riskiest part of many supply chains is not the ocean transit—it’s the time in containers, yards, docks, and staging areas where temperatures can spike.

Buyer actions that reduce shipping-related oxidation risk

- Plan seasonal shipments: avoid peak heat windows for long routes if possible.

- Reduce dwell time: fast pickup at destination and efficient receiving reduce exposure.

- Align packaging to lane: stronger barrier and oxygen control for long, warm, or delay-prone lanes.

- Set shelf-life buffer: match your purchase timing to your consumption plan so product doesn’t sit after arrival.

Troubleshooting oxidation complaints: a practical root-cause map

When an oxidation complaint occurs, move from broad to specific. The goal is to identify whether the issue likely started before packing, during storage/shipping, or after opening at the plant.

Step 1: Confirm basics

- Lot code / pack date / receipt date

- Storage conditions at your facility (temperature, staging time)

- Whether bags were opened and resealed (and how long they remained open)

Step 2: Ask supplier program questions

- What was the storage temperature before shipment?

- What packaging and liner were used for this lot?

- Was the lot held or staged unusually long before load-out?

- Were there any known issues in this production window?

Step 3: Map to likely causes

- Early off-notes immediately upon opening: could indicate pre-pack aging, poor storage prior to shipment, or oxygen exposure in packaging.

- Off-notes after time opened in plant: often points to internal handling and resealing discipline.

- Off-notes after long transit or summer shipments: often indicates heat exposure in the logistics chain.

Most teams find that a consistent storage and resealing protocol prevents the majority of “mystery” oxidation issues.

FAQ

Do walnut pieces oxidize faster than halves?

Often, yes—because pieces generally have more exposed surface area. That doesn’t mean pieces are “bad,” but they typically benefit from stronger packaging, cooler storage, and faster turns.

Can light exposure really matter in a warehouse?

Yes, especially if pallets are staged near doors or in bright areas for long periods. Light is usually a smaller driver than temperature, but it can accelerate oxidation and should be treated as a controllable variable.

What’s the best single thing a buyer can do?

Treat storage temperature and oxygen exposure as part of the product. Choose packaging that matches your lane and shelf-life target, then enforce a simple internal rule: keep walnuts cool and sealed, and minimize time open to air.

Next step

If you share your application and the format you need, we can confirm common spec targets, packaging options, and the fastest supply lane. Use Request a Quote or email info@almondsandwalnuts.com.

To reduce back-and-forth, include: walnut format (halves/pieces/meal/flour/oil), target color/defect limits, moisture target, packaging preference (liner/barrier/vacuum/nitrogen), volume, destination, and timeline.

Quick links: bulk walnut products • products catalog • contact